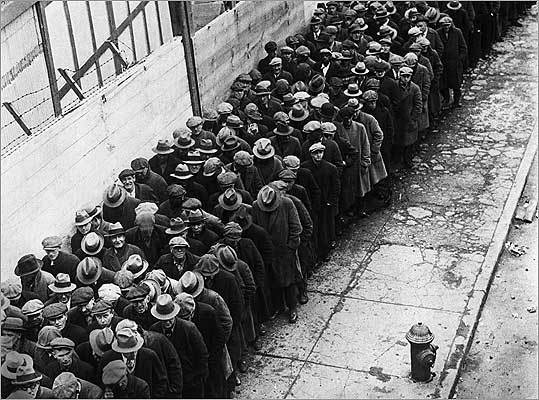

The big brass of the Big Three have just arrived on Capitol Hill for a reprise of last month’s appearance before the Senate Banking Committee. For this round, they rolled up in cars—a supposed act of contrition after last month’s corporate jet flap. As a metaphor for the auto industry’s humble new attitude, this reversal had a made-for-TV shine. However gratifying it might be to watch corporate CEO’s give up their corporate jets—if only temporarily and for PR—there is another metaphor that comes to mind this morning.

Two weeks ago, Congress told the automakers to come back with a plan detailing how they could remain viable in the long term. Republican senator Michael B. Enzi from Wyoming expressed doubt that the $25 billion that the industry sought then (they’ve upped it now to $34 billion) “will do anything to promote long-term success.”

The same might be said of the efforts of the United States to recover from the crisis in the financial industry that has spurred recession and threatens to vaporize the jobs, savings, and spending power of millions of Americans.

What are we doing to promote our own long-term success?

The bailout plan that Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson proposed last September called for the buying up of so-called toxic assets, mortgage-backed securities and the like. By the time Congress and President Bush approved the plan in October, it had morphed. Paulson used the first $250 billion to inject money directly into banks, giving nine of the largest $25 billion apiece. Now, the Treasury has shifted its efforts toward trying to lubricate the lending process by lending $200 billion to private investors who buy up consumer debt (credit card, student loans, small-business loans, auto loans, etc.). The Fed also plans to buy up $500 billion of mortgage-backed securities from Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, and Ginnie Mae, the nation’s “big three” mortgage buyers.

The goal of these massive outlays of cash is to unfreeze credit. Consumer spending is down—way down—and economists rightly worry that we’ll be kicked into a downward spiral of job losses and economic contraction.

So what we are doing is what we’ve done in one way or another for most of the twentieth century: throw everything we can at spurring economic growth.

Granted, our approach to this task has changed over the years. John Maynard Keynes helped us realize in the forties that more growth could be squeezed out of the markets if the government primed the economic pump through expenditures and ironed out the low periods through regulation. In the eighties, we lost patience with regulation. Milton Friedman and his coterie at the University of Chicago pushed for deregulation and the freeing up of markets. In true neoclassical style, we put our faith in the “invisible hand” of the market to maximize efficiency and economic growth. Now, with financial crisis upon us, we are frantically attempting to prime the economic pump and are once again talking about regulation.

But whether we’re bent on regulation or deregulation, government intervention in the markets or nonintervention, our society focuses with laser-like precision on one goal, the one panacea on which nearly everyone of our time can agree: growth.

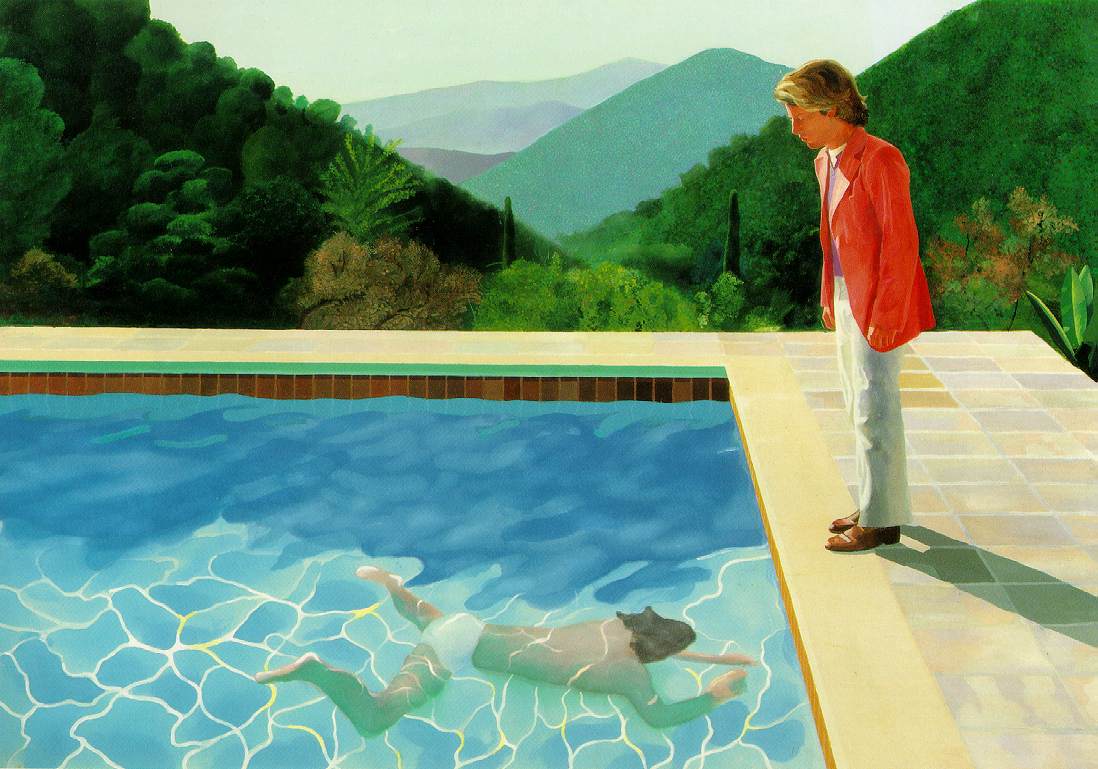

Indeed, growth can be a good thing. It has helped most of us to meet our basic needs. It allows for upward mobility. It tickles us with a constant stream of innovative and alluring products. It sweeps away uncomfortable questions about the distribution of scarce resources.

But growth has a downside. Foremost is the ecological toll it takes on the planet. All that stuff we consume, all that energy we burn, comes at a cost to the livability of the earth. Until recently, it was easy to ignore growth’s negative side effects. The fabulous schwag that came with a rapidly expanding economy easily outshone the pollution and impoverishment of the natural world. Now, however, scientists tell us that the damage we are doing is much more than aesthetic. Indeed, if unchecked, this damage will eventually lead to a series of converging crises. Meanwhile, the benefits we receive from each annual percentage point growth in GNP continue to diminish. (What do you buy for the nation that has everything?)

Members of Congress chastised the Big Three automakers for not responding to consumer demands, for imagining that gasoline would remain cheap, for tolerating so much bloat—for concentrating so much on pumping out the sheet metal that they failed to adapt to new realities.

But we Americans are guilty of the same lack of vision. Like U.S. automakers, we have been slow to adapt to changing realities. Our slavish devotion to economic growth at any cost was what got us into this crisis, and more growth is the only cure we have been able to imagine to get us out.

Attempting to solve our current financial crisis by focusing only on propping up economic growth—the cycle of consuming ever more—will backfire in the long run.

We are deep in a financial crisis. We can either take this opportunity to examine how we got here and where we are headed, or, like the Big Three, we can try to wheedle more money out of the system to keep on doing what we’ve always done, which, if current scientific consensus is correct, will probably end very, very badly.

What might our kids ask us when we hand them a world warmed over and out of whack?

What were you doing to promote long-term success?

Well, ah, not much. We, um, tried to get the folks to buy more stuff for the holidays.Pivotal moments seem to pop up all the time these days, but this one is especially important. We can start measuring our success not by how much the economy grows, but by our quality of life. Or we can head at full speed down the growth-at-any-cost path and pay the price later. And next time the world financial system may not feel like lending us the trillions we need to re-prime our economic pump.

If this financial crisis demonstrated one thing, it is that even those at the top (perhaps especially those at the top) don’t really know what they’re doing. They’re winging it like everyone else.

Just as Congress sent the automakers back to Detroit to come up with a long-term plan, we need to send lawmakers back to the drawing board to come up with a viable plan for our own long-term success. While we can’t expect to turn our vast and complex nation around overnight, crisis has a way of speeding up change and opening up new possibilities.

We need to raise our expectations and insist that our political leaders articulate a vision of long-term success.

The good thing about this financial crisis is that we’ll probably live to deal with another one; we can learn from our mistakes. The bad thing about the global ecological crisis we face is that we only have one chance. If we humans botch this one, we’ll be paying the price for a very long time.

If we are so lucky.